Originally published on LinkedIn on September 5, 2020

I recently stumbled on an associate’s supposed comedic video in which he explains social inequity from the point-of-view of the Joker of Batman fame. His premise was we shouldn’t condemn those we perceive as “bad guys,” whether it be the super-rich, Nazi sympathizers, police officers with double standards, people with differing political beliefs or those with different colored skin.

This stance, he reasoned, prods us to rise up against those we see as “bad.” Otherwise, if we go along with the system, we’re viewed as complicit in a system that is inherently hierarchical and racist. He concluded, we should simply have decency towards humans and not separate them into “good” and “bad” for all people have been harmed.

It’s a lot to unpack.

Social inequalities have always existed. There’s always been the rich, the poor, and those in-between. Imbalances will continue to exist with birthright, demographics, intelligence, opportunity, and luck continually tipping and readjusting the scales of one’s life.

Inequality isn’t the lone issue. It’s inequity, lack of fairness or justice.

“You must not lose faith in humanity. Humanity is an ocean; if a few drops of the ocean are dirty, the ocean does not become dirty.” Mahatma Gandhi

Last September, Jeff Bezos, the richest man in the world, cut health benefits for part-time workers at his grocery store Whole Food. The savings were equivalent to what he makes in less than six hours.[1] On August 13th of this year, Jeff Bezos was worth $189.4 billion, a 68% increase since March 18,[2] yet, Amazon is notorious for their demanding, often unsafe, working conditions, and less than generous benefits, including paid time off for those who are sick or need to self-quarantine due to COVID-19.

Is it wrong, even bad, for one man to hold so much wealth while his workers suffer? Countries where there’s more equality and equity, such as Sweden, Norway, Germany, Czech Republic, and Austria, offer higher qualities of life with citizens able to add value rather than struggle to simply survive.

It’s the philosophy that a rising tide lifts all boats. When people have more disposable income they spend it at local restaurants and stores, purchase and fix up their homes, invest in themselves and their children’s future, and attend to their medical issues before they evolve into chronic conditions that require hospitalization. Additionally, tax revenues increase, providing funding for infrastructure, health and social services, education and training, housing, and much more.

Unfortunately, in America, the rising tides aren’t evenly distributed, and typically only elevate those in the upper echelons.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, people of color fill a disproportionate number of low-paying agriculture, domestic, and service jobs, such as baggage porters, bellhops, barbers, food servers, taxi drivers, and chauffeurs, grounds maintenance workers, maids, and housekeepers.[3] These jobs typically don’t come with benefits, forcing people to work when they’re sick rather than stay home.

Additionally, most of these jobs can’t be done remotely. Studies show only 35.4% of Blacks and 25.2% of Latinos can do part of their work remotely, compared with 43.4% of Whites.[4] It comes as no surprise that Blacks account for 42% of coronavirus deaths so far, despite representing only 21% of the population.[5] Many have jobs that don’t enable them to safely work from home coupled with living in multi-family environments where it’s difficult to quarantine if they do get sick.

Similarly, CNN reported Latinos comprise 60% of COVID-19 cases and 48.5% of deaths in California even though they are only 39% of the population. A key issue is that Latinos are essential workers with many of them concentrated in California’s Central Valley, often, with three generations living in the same trailer or apartment. Additionally, social disparities, an increase in underlying medical conditions, such as diabetes, along with limited access to healthcare contribute to their higher infection rates and fatalities.

Decades before coronavirus ripped the band aid off the wound of inequality and inequities, there have been deep rooted issues. In the second quarter of 2019, Black homeownership was at a record low of 40.6% compared to 76% for Whites, 61.4% for Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, and 51.4% for Latinos.[6] Even in cities where there’s a large Black population, the gap between Black and White home ownership is 20 to 25%, owing to years of unfair policies and discrimination from access to quality schooling and education to high-paying job opportunities.

A statistic that’s recently been bandied is the disheartening disparities in wealth with the net worth of typical White families ($171,000) being nearly ten times greater than that of Black families ($17,150).[7] It’s easy to jump to conclusions, but the reality is 38.1 million, nearly 12% of Americans lived in poverty in 2018, including 25.4% of Native Americans, 20.8% of Blacks, 17.6% of Hispanics, and just 10.1% of Whites.[8]

The United Way tracks people who earn above the Federal Poverty Level, but not enough to afford a bare-bones household budget. These people, known as ALICE (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed), can comprise up to 33% of a state’s population. In Mississippi, for instance, 20% of people live in poverty with 30% considered ALICE. The possibility of getting a job that lifts them out of “just getting by,” let alone accumulate wealth is out-of-reach for half the population.

Even in larger states with more opportunities like California, Texas, Florida, and New York, 43 to 47% of the population lives in poverty or is considered ALICE.

These inequities aren’t new. They’re decades, and in some cases, centuries old. They’ve been percolating, creating pressure points, and then bursting, sometimes creating a whimper. Other times, a loud outburst with people taking to the streets.

The discourse, surrounding the Affordable Care Act (ACA), shown a light on pre-existing conditions, lack of access to basic preventive care, disparities in care facilities, and the unacceptable number of Americans who go bankrupt due to healthcare expenses, and in many cases, pass away because they couldn’t afford care.

A collective sigh could be heard across America when the ACA passed in 2010 and was saved from being repealed in 2007.

While millions have benefited, the act has been on shaky ground as the Republicans have slowly chipped away at it, instead of making it stronger and more inclusive. Once again, people are having to break out their orange crates and evangelize healthcare as a human right.

Black Lives Matter, and the myriad of other social injustices that plague America, is similar. Advocates have been standing on orange crates for decades, shouting for reform, acceptance, and fairness. They’ve lobbied, used the media to create awareness, and turned to public figures and celebrities to evangelize their causes. But it hasn’t worked.

“The day the power of love overrules the love of power, the world will know peace.” Mahatma Gandhi

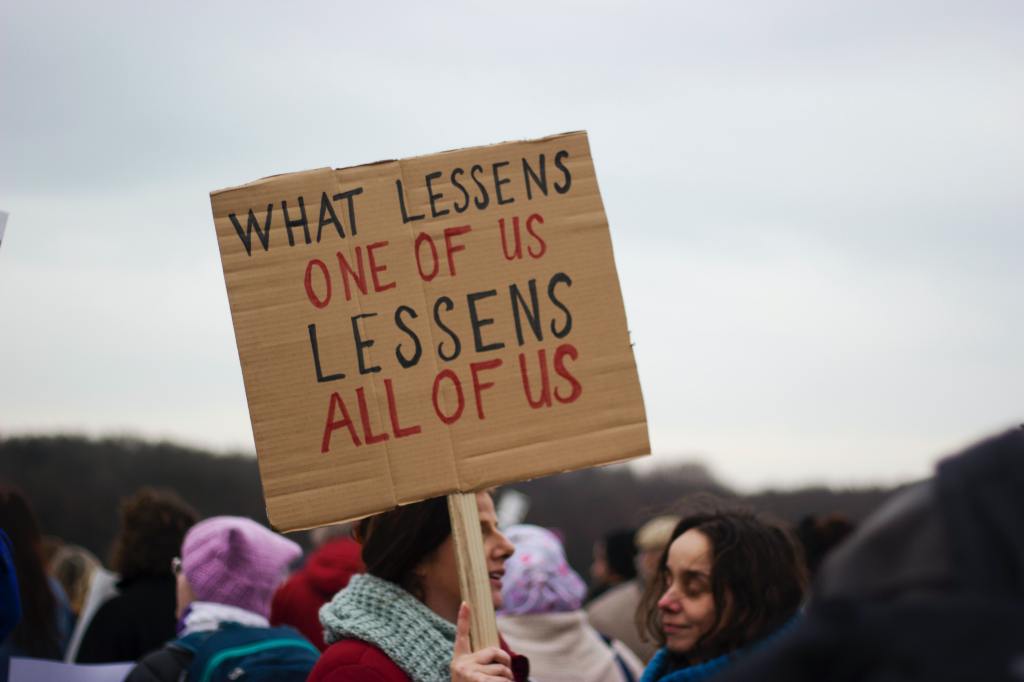

The next step isn’t to “stand down,” but stand up, taller, louder, and bigger. It’s peacefully organizing and showing solidarity through protests, sit-ins, and boycotts. It’s being brave in the face of dissent and having the conviction to defend those who are disadvantaged or don’t have a voice. It’s learning from history, applying the best practices, and discarding those that are destructive.

It’s having a moral compass that points towards kindness, justice, and altruism. It’s not being afraid to judge good from bad, and right from wrong. Because school shootings, Fascism, wanton violence, blatant discrimination, and taking advantage of workers will never be good or right.

It is not, by any means, looting, setting fires, destroying others’ property and lawlessness. As Indian civil rights icon Mahatma Gandhi once said, “An eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind.”

Instead, as Gandhi wrote, we should strive to “be the change you wish to see in the world,” pushing for more equality and equity in our communities, states, and country.

Thank you to Micheile Henderson for her photo on Unsplash

[1] Cutting Health Benefits of 1,900 Whole Food Workers Saving World’s Rich’s Man Jeff Bezos What He Makes in Less than Six Hours, Common Dreams, Eoin Higgins, September 17, 2019, https://www.commondreams.org/news/2019/09/17/cutting-health-benefits-1900-whole-food-workers-saved-worlds-richest-man-jeff-bezos

[2] Twelve U.S. Billionaires Have a Combined $1 Trillion, Inequlity.org, Chuck Collins, Omar Ocampo, August 17, 2020, https://inequality.org/great-divide/twelve-us-billionaires-combined-1-trillion/

[3] Systemic Inequality and Economic Opportunity, Center for American Progress, Danyelle Solomon, Connor Maxwell, and Abril Castro, August 7, 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2019/08/07/472910/systematic-inequality-economic-opportunity/

[4] How COVID-19 Is Affecting Black and Latino Families’ Employment and Financial Well-Being, Urban Institute, Steven Brown, May 6, 2020, https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/how-covid-19-affecting-black-and-latino-families-employment-and-financial-well-being

[5] 7 ways 2020 has exposed America, Salon, Robert Reich, June 23, 2020, https://www.salon.com/2020/06/23/7-ways-2020-has-exposed-america_partner/

[6] Why the homeownership gap between White and Black Americans is larger today than it was over 50 years ago, CNBC, Courtney Connley, August 21, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/08/21/why-the-homeownership-gap-between-white-and-black-americans-is-larger-today-than-it-was-over-50-years-ago.html

[7] Examining the Black-white wealth gap, Brookings, Kriston McIntosh, Emily Moss, Ryan Nunn, and Jack Shambaugh, February 27, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/02/27/examining-the-black-white-wealth-gap/

[8] The Population of Poverty USA, PovertyUSA.org, https://www.povertyusa.org/facts